The psychological tricks used to help win World War Two

British Library Board

British Library BoardWhat did the British government learn from Mein Kampf? And how did they deal with the idea of ‘the enemy within’? Fiona Macdonald finds out from a new book about British propaganda.

British Library Board

British Library BoardThe word ‘propaganda’ might suggest some form of misinformation – yet in boosting morale during World War Two, the British government had to maintain a careful balancing act. While employing a range of psychological tricks, they had to be seen to be as truthful as possible. “The Ministry of Information (MOI) had been disbanded immediately after World War One because official propaganda had become too easily associated with lies and falsehood,” historian David Welch, author of the new book Persuading the People: British Propaganda in World War II, tells BBC Culture. “In World War Two when the MOI was re-established the Ministry was acutely aware of the cynicism associated with propaganda. It was agreed that, with the exception of harmful and unbelievable truths, whenever possible the truth should be told.”

British Library Board

British Library BoardFormer Director General of the BBC John Reith was appointed Minister of Information in 1940. “He laid down two fundamental axioms for the balance of the war: that news equated to the ‘shock troops of propaganda’ and that propaganda should tell ‘the truth, nothing but the truth and, as near as possible, the whole truth’,” says Welch. That didn’t stop the MOI relying on tried and tested techniques to manipulate public opinion. A report commissioned by Chatham House in 1939 established 86 ground rules for doing so, such as “propaganda should fit pre-conceived impressions, e.g. a Chinaman thinks every foreigner a cunning person who is prepared to use a concealed gun should wiliness fail”.

In Persuading the People, published by the British Library, Welch writes: “interestingly, [the rules] reveal that those who drafted the secret document were familiar with Hitler’s view on propaganda published in Mein Kampf (‘My Struggle’). Not only that, but they appeared to endorse some Hitlerite propaganda principles. For example, the document talks about appealing to the instinct of the masses rather than to their reason, and stresses the importance of building on slogans and the need for repetition.”

British Library Board

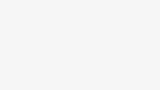

British Library BoardThe posters, pamphlets and films included in Persuading the People reveal the range of approaches the MOI used throughout World War Two. One of them went by the title of the “Anger Campaign”. “The MOI had initially decided that ‘truth’ should be the main weapon with which to attack the enemy in the minds of the public,” writes Welch. “However, after the bitter and dramatic events in the summer and autumn of 1940, the MOI launched its Anger Campaign and British propaganda took a more drastic approach by emphasising the brutality of Nazi rule.”

In the war’s early period, within the MOI there was “an impatience and an implicit lack of confidence in the public – a belief that they were, according to Lord Macmillan, the Minister of Information, ‘patient, long-suffering, slow to anger, slower still to hate’… that the working man in particular had little comprehension of the consequences of a Nazi victory and was, therefore, in need of a sharp dose of stiffening.”

The Anger Campaign aimed to deliver a shock that could break through what the MOI saw as a “dangerous complacency” with lines like “The Hun is at the gate. He will rage and destroy. He will slaughter women and children”. In a radio broadcast by the author JB Priestley for the BBC General Overseas service, Priestley described the ‘bright face’ of Germany: music, art, and beautiful landscapes. But, he warned, “after the Nazis came … the bright face had gone, and in its place was the vast dark face with its broken promises and endless deceit, its swaggering Storm Troopers and dreaded Gestapo, its bloodstained basements”.

British Library Board

British Library Board“The ordeal of Total War – even more so than the Great War – required that civilians must also ‘fall-in’ and participate (and possibly suffer) on a massive scale in the war effort,” Welch tells BBC Culture. “Morale came to be recognised as a significant military factor and propaganda emerged as an essential weapon in the national arsenal. Really for the first time, World War Two witnessed a ‘people’s war’ that was every bit as important as the war fought on the fighting front.”

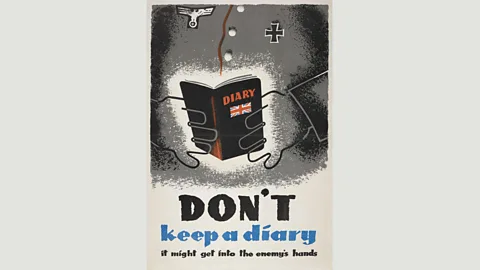

Part of that involved alerting the public to spies in their midst. The fall of France and the Dunkirk evacuation, writes Welch, “gave rise to the belief that a ‘Fifth Column’ had been operating as an advance guard for the German army”. The MOI’s “Careless Talk Costs Lives” campaign focused on the idea of an ‘enemy from within’ and urged people to be discreet. “As a last resort they were asked to inform the police about indiscreet characters such as ‘Mr Secrecy Hush-Hush’, ‘Miss Leaky Mouth’, or ‘Mr Pride in Prophecy’,” writes Welch.

British Library Board

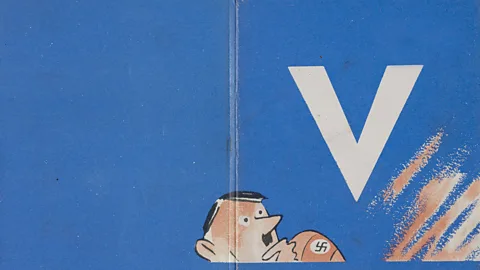

British Library BoardOne of the most successful campaigns, “V for Victory”, was launched by the BBC in July 1941. “It was inspired by Victor de Laveleye, former Belgian Minister of Justice and director of the Belgian French-speaking broadcasts on the BBC, who urged his countrymen to use the letter V as a ‘rallying emblem’ since it is the first letter of the French word for victory (victoire), the Flemish and Dutch words for freedom (vrijheid) and, of course, the English word ‘victory’, making it a multi-national symbol of solidarity,” explains Welch. The campaign urged listeners in Nazi-occupied Europe “to show their support for the Allies by scrawling the letter V wherever they could.”

British Library Board

British Library BoardThe Morse code for the letter V (dot-dot-dot-dash) appeared to be echoed in the first four notes of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony; Douglas Ritchie of the BBC’s European service made it the theme song for his radio programme. “Listeners began to replicate the sound any way they could as a symbol of resistance,” writes Welch. “Across occupied Europe, people daubed the V symbol and tapped out the sound to show their solidarity.” While the slogan was aimed at the occupied nations, says Welch, “it took off in Britain. On 19 July 1941, Winston Churchill referred approvingly to the campaign in a speech – from which point he started using the V hand sign.”

British Library Board

British Library BoardThe government had relied on ‘atrocity propaganda’ during World War One, which “focused on the most violent acts committed by one’s enemy – especially the numerous violent acts against civilians perpetrated by the ‘Hun’,” says Welch. But this had backfired. “The British public in the inter-war period came to the conclusion that these stories had been fabricated or exaggerated.”

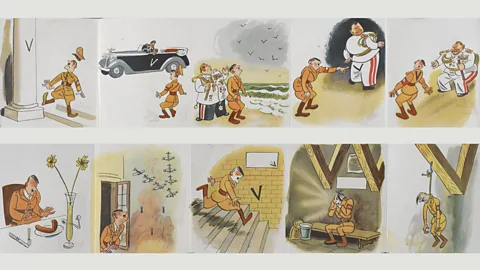

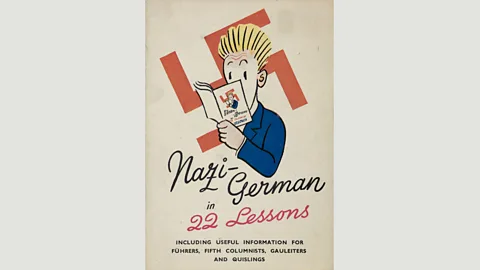

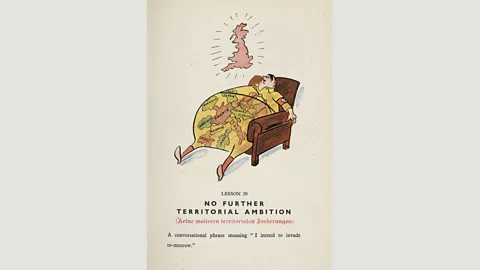

And so, after emphasising Nazi brutality in its Anger campaign, the British government found ways to skewer their enemy through satire: “much of British propaganda in World War Two was characterised by the use of humour to deflate the enemy.” Welch cites comedy radio programmes such as Tommy Handley’s It’s That Man Again (ITMA), in which Handley was the Minister for Aggravation and Mysteries at the Office of Twerps. “ITMA found a place in people’s hearts because it punctured pomposity… The characters became larger than life and their catchphrases were etched into the fabric of everyday life.”

British Library Board

British Library BoardWelch also describes something that wouldn’t be out of place on today’s social media: “In 1941, film-maker Charles Ridley cleverly re-edited for the MOI real footage of goose-stepping Nazi soldiers at Nuremberg (taken from Leni Riefenstahl’s film of the 1934 Nazi Party Congress, Triumph of the Will) to the popular tune of The Lambeth Walk.” The film, Germany Calling, was shown as a newsreel.

“By speeding up the film, the incipient threat of the SS was diluted and their formations – directed by a preposterous-looking Hitler – rendered comical, in a silent-film tradition,” writes Welch. “The reduction of a frightening enemy to the level of visibility and ridicule, as in this lampooning of Hitler and his forces, is, in psychological terms, a means of achieving power over him.”

British Library Board

British Library BoardPreaching to the converted

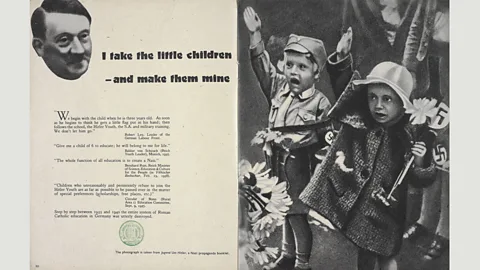

“The MOI used the notion of the barbarous Hun – first exploited on a massive scale in World War One – to show that they were still the ‘same aggressor’,” Welch tells BBC Culture. “It could then use existing information about how the Nazis treated non-Aryans and subverted the educational system for their own ideological ends, and their attitude to religion.” The MOI exposed the Nazi persecution of German clerics who had questioned Nazi rule, such as Bishop Clemens August Graf von Galen of Münster, who delivered sermons denouncing Gestapo lawlessness. The RAF dropped copies of the bishop’s sermon – banned in Nazi Germany – throughout the Reich, and it was reproduced in a publication called Gestapo v. Christianity.

This image, with the photo taken from a Nazi propaganda booklet Jugend Um Hitler (or Youth Around Hitler), featured in the pamphlet They Would Destroy the Church of God. Striking images were placed alongside text that accused the Nazis of paganism, Führer-worship, and the perversion of children’s education. “The focus was on how Nazi Germany was undergoing an anti-Christian form of indoctrination,” says Welch. “The notion of freedom of worship was closely related in British propaganda to freedom of thought.”

British Library Board

British Library BoardTurning an enemy into an ally

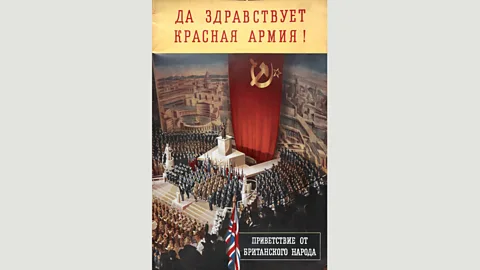

While the MOI played on existing stereotypes for some of its campaigns, it needed a different approach for others. “Stereotypes proved more difficult in the case of the USSR (an enemy turned ally),” says Welch. “The MOI got round this by largely ignoring the Soviet ideology and concentrating on ‘comradeship’ and fighting a common enemy – ‘Their Fight is Our fight’.”

This poster says “Long Live the Red Army! Greetings from the British People”. After Soviet forces recaptured Stalingrad in February 1943, the MOI organised an evening of celebration at the Royal Albert Hall with readings from Laurence Olivier and John Gielgud. The government declared a “Red Army Day”, marked in British cities with pageants and music. “Joseph Stalin, who had previously been depicted in British propaganda as a deceitful and conniving dictator, was suddenly transmogrified into an avuncular ‘Uncle Joe’,” writes Welch. “By focusing on the courage and fighting spirit of the Russian people and presenting Joseph Stalin as an avuncular nationalist, British propaganda was able to sidestep any possible inconsistencies with its treatment of the Soviet Union in the pre-war period.”

This story is a part of BBC Britain – a series focused on exploring this extraordinary island, one story at a time. Readers outside of the UK can see every BBC Britain story by heading to the Britain homepage; you also can see our latest stories by following us on Facebook and Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.